When Swimming Culture Called “In Lane 4, 6.1.20” Instead Of Legend Leisel Jones

2020s Vision: Swimming Culture. On a day when Denmark apologised to its swimmers for the harm caused by practices including weigh-ins at which girls and young women athletes were called fat and humiliated in front of their teammates, including boys and men, we take the moment to reflect on lessons learned from history.

Revelations from Aussie breaststroke legend Leisel Jones are what we focus here but the issues she raised on her way to the International Swimming Hall of Fame are universal. Both coaches cited in the report of the investigation into Danish swimming today were coaching, including roles in Australia, at the time Jones was excelling.

There has been a shift in swimming culture since but if the darker side of what you read below is familiar to you today, you’ll know it’s wrong. As you read, consider the nature of what’s wrong: it isn’t measuring weight for weight, like angles of buoyancy and much else, does matter in performance swimming. Rather it’s down to how and in what circumstances weight is measured and what happens next.

We start with memories of the fine outcomes, the stuff that unfolds with smiles and tears under bright lights – before we peak behind the curtain at what was endured alongside the hard word and good guidance she also received.

Lethal Leisel – A Champion … and Survivor Of Practices Long Past Their Sell-By Date

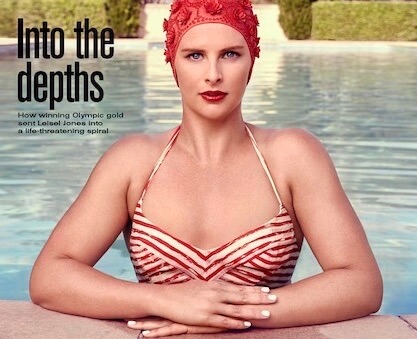

Leisel Jones on the cover of Good Weekend Magazine in Australia when the publication plunged Into the Depths of swimming culture – Photo Courtesy: Good Weekend

‘Lethal’ Leisel Jones glided on to high plinth in the Pantheon when she entered the International Swimming Hall of Fame (ISHOF) as a member of the Class of 2017.

There was so much to celebrate. When she raced at her last Games, at London 2012, Jones became the first Australian swimmer to compete in four Olympic Games and, alongside Ian Thorpe, holds the record for the most Olympic medals (9) won by any Australian. There were also seven golds at the World Championships and six long-course world records in the mix, three over 100m and three over 200m breaststroke.

Leisel Marie Jones was born on August 30, 1985. As a ten year-old Brisbane school girl, she watched Samantha Riley* win the bronze medal in the 100m breaststroke at the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta. Less than four years later, she ousted her idol from the Australian Team by winning the 100m breaststroke at the 2000 Australian Olympic trials at the age of 14.

The ISHOF citation includes this: “Soon after her fifteenth birthday, she wowed a home crowd to claim silver medal in the 100m breaststroke and added another silver in the 4 x 100m medley relay at the Sydney Olympic Games.

“For the next eight years, Liesel was the most dominant woman breaststroker in the world. Named world swimmer of the year in 2005 & 2006, the pinnacle of her career came with her individual gold medal in the 100m breaststroke, silver medal in the 200m and a second gold medal in the 4 x 100 medley relay at the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games.

The cover of Liesel’s book “Body Lengths” -Penguin Books

Nicknamed “Diesel” and “Lethal Leisel,” she candidly recounts in her 2015 autobiography, Body Lengths, that her achievements were not without their challenges. In her book she tells what it was like to be thrust into the limelight so young and under constant pressure from an early age to be perfect — from coaches, from the media and from herself. Despite the highs of her swimming stardom, she suffered depression, and at one time planned to take her own life. In London, she was criticized in the media for her weight, but she handled herself with great composure.

“She has emerged with maturity and good humor, having finally learnt how to be herself and live with confidence. She also hopes that by telling her story, other female athletes will understand they are not alone.”

From The Archive – How Lethal Leisel Showed The Way

Leisel Jones on the cover of Good Weekend Magazine

Jones, honours stretching to three Olympic golds among nine medals, seven world-championship golds among 14 global long-course medals, 10 Commonwealth golds and six world long-course records over 100 and 200m breaststroke (3 each), entered the Sport Australia Hall of Fame in 2015.

Australians got a glimpse of her before the world saw a 15-year-old claim silver a whisker from gold in the 100m at the Sydney 2000 home Olympic Games. The racing ended at London 2012, a fourth Games and the end of a period in Jones’ life that brought both elation and depression.

“This is just a really nice cherry on the top of what has been a pretty terrific ride,’’ Jones told the Herald Sun.

Jones’s nine Olympic medals matched the record tally of Ian Thorpe for the most medals won by an Australian at a Games. Her highlight was the Olympic 100m crown at Beijing in 2008.

It was far from plain sailing. Reading extracts from her new book “Body Lengths“, you might well think the title could have been Body Blows.

It was far from plain sailing. Reading extracts from her new book “Body Lengths“, you might well think the title could have been Body Blows.

It was back in 2006 when Jones first revealed that she had suffered depression as a result of the pressure on her from a young age. She was 20 and at a social function she said:

“I just hated the person I was when I was 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 – being thrust into the limelight and being told to grow up now was incredibly hard.”

Earlier that year, on March 20, she rewrote the pace of women’s breaststroke with a 1:05.09 world record. Talk of axes, shattering, smashing and sledgehammers was the order of the day, while the gap between Jones and those chasing was starting to take on swimming’s equivalent of Biblical proportions.

How all rivals saw Leisel Jones for several seasons at the height of her career – by Patrick B. Kraemer

The time would have won the world title in Kazan, 2015, almost a decade on.

It came off a 30.83sec split, which at the time would have won her the silver behind her own gold in the 50 metres straight at the Commonwealth Games in Melbourne.

Jones, after screaming at the scoreboard, padded over to we the media deckside with a beamer of a smile on her face and said:

“I was going for the world record . . . but I wasn’t feeling my best all week, so it was hard to determine what would happen. I could not believe it. I went into shock. I’m still in shock. I don’t think I’m unbeatable – nobody is.”

The time did not withstand the excesses of shiny suits but in textile survived four years until the 200m Beijing champion, Rebecca Soni (USA) became the first to crack 1:05, with a 1:04.93 at the Pan Pacific Championships in 2010. Since then, Ruta Meilutyte (LTU), 2012 Olympic champion, has moved the pace on to 1:04.35.

Jones was coached by Stephan Widmer, of Swiss origin, for much of her elite career, and also worked with Rohan Taylor – who described her as a “once-in-a-generation type of athlete who’s exceptionally gifted in her event” – on the way to Olympic glory. She perfected the art of reducing the dead zone in breaststroke to a negligible level.

It took time to get there. Emerging from her 1:05.17 victory by more than a body length at Beijing in 2008, she said: “It’s been a long journey, a long eight years.”

Even before Jones qualified for her first Olympic team, her first elite coach Ken Wood had told her she would be the world’s best breaststroker, but the way to her destiny was harder and more circuitous than she or anyone could have imagined.

Jones pressed the button of timewarp on breaststroke in the 2006-07 seasons, here a fine example of her pace, power and smoothness of skill:

After a stunning Olympic debut in Sydney, Jones was beset by self-doubt, unable to find self-esteem in medals and records alone.

The experiences she went through would be helpful to others when she became the face of Swimming Queensland’s campaign ‘Growing Up In Lycra‘, issues of body shape and self-image to the fore.

Jones reached her low point when she entered the Athens Olympics four years after Sydney promise and now as the world record-holder and gold medal favourite – only to be beaten by China’s Luo Xuejuan and fellow Australian Brooke Hanson. Jones once said:

“I was probably as low as you can possibly get after Athens. As swimmers, we have once every four years a major competition and when you are told before that you are the best and you can’t be beaten, and then you are beaten, it’s devastating.”

Jones was branded a choker, salt rubbed in wound by Olympic legend Dawn Fraser, who described her as a “spoilt brat” after she showed her disappointment on the medal podium in Athens.

Jones returned home with a stark choice: retire or change approach and attitude. Jones chose swimming to win. She parted company with Wood to work with Widmer in a squad that included Libby Lenton. [Photos: Stephan Widmer and Leisel Jones on Mare Nostrum Tour, 2006 – by Patrick B. Kraemer]. The Swiss coach saw Jones as a girl “who didn’t know who she was”, wrote Nicole Jeffery in The Australian.

A different swimmer showed up at world titles in Montreal, northern summer 2005. Between her first 100m world title and Olympic glory in 2008, she would win every race she entered – and most by vast margins well ahead of the curve of her opponents. Even so, the 2005 win was seen as “difficult”. Jones would later say:

“In Montreal it was very, very difficult. It was still fresh after Athens, I was still hurt and a little low. I was still searching for myself and finding my self-worth and learning to believe in myself. I learned so much there. In terms of personal experience and personal growth that was more important than this. To overcome the difficulties there, because I was still copping criticism and I was still learning … that was the first time I enjoyed racing.”

Leisel Jones by Patrick B. Kraemer

On the way to Beijing, she matured mentally, met the man she would become engaged to, former AFL player Marty Pask (the partnership was called off beyond Beijing in November 2008) and switched coaches to Taylor, who guided her to Olympic gold.

In her autobiography Body Lengths, Jones does not hide her contempt for the culture she was subjected to.

Beyond her Beijing bonanza, Jones swam on to London 2012 but her fastest swimming days were behind her. She arrived in Britain for her last Games as an athlete still capable of a place on the podium – and indeed she returned home with a silver with teammates in the medley relay. Her time in London was asked, however, by a woeful concentration in the Australian media on her weight and body shape.

Leisel Jones with teammate Mel Schlanger (now Wright) – by PBK

Leisel Jones with Libby Trickett (nee Lenton) – by PBK

That last experience in the pool before retirement on November 16, 2012, fed into the concurrent theme in Body Lengths: Jones calls it the “irresponsible and terribly damaging” effect swimming had on her body image and mental health.

There were many joyous moments to savour down the years but “pressure to be perfect” was what she felt – from others and self, her career marked by the ever-present weigh-in from 15 years of age through to Olympic swansong 12 years later.

She was “actively encouraged” to skip meals in an effort to lose weight as a teenager and often felt ridiculed in front of her peers at thrice weekly weigh-in’s where coaches used code words to call the young athletes “fat”. She writes:

“Whenever I have to stand on the pool deck in my togs, listening to my body being discussed like it’s an engine and not the arms, legs, thighs and stomach of a teenage girl, I am self-conscious and miserable.”

Girls Labelled A 6:1:20 – Bloke Code For ‘FAT’

At 30 in 2015, Jones said that she would often sob in the showers after the weigh-in, which unfolded with men “as old as our dads” passing judgement and labelling some girls “a 6:1:20”. “This is their code, their secret talk,” she writes.

“They think we don’t understand when they call a girl – it’s always a girl – a ‘6:1:20’. But when she’s crying in the showers later, it’s because she knows that ‘6’ stands for the sixth letter of the alphabet, ‘1’ the first, and ‘20’ the twentieth. F. A. T.”

Leisel Jones – by Patrick B. Kraemer

The Sydney Morning Herald depicting 15 year old Leisel Jones at Sydney 2000

Jones said she never learnt how to develop a healthy relationship with food as the team was not given “sustained scientific dietary advice”, aside from the recommendation to use meal-replacement shakes to shed a few kilos. She writes of crash-dieting and her own responsibility for the roller-coaster that placed her on:

“It’s a quick way to screw up a teenage girl’s metabolism, to say nothing about the state of her head. It was all my own idea and it nearly killed me – very nearly broke my spirit – but I’m sure it went some way towards keeping the kilos off.”

Body Lengths – A Short Extract

In her diary style book, Jones recalls from a time of training:

“I don’t drink, I don’t eat cheese. I skip ice-cream, hot chips, burgers and pies. The sight of a piece of mud cake can reduce me to tears, worse if it has chocolate icing. I am always on a diet, always counting calories, obsessing over food, and always, always hungry. I am insatiable. I cannot eat enough. I am still a teenager, with a break-neck teenage metabolism, and after swimming and training for hours each day, I can never seem to fill myself up. And yet I still try to diet.”

First world titles in 2005 – by Patrick B. Kraemer

“Last year was ‘My Year Without Chocolate’, in which I didn’t eat a single square of chocolate. Not one piece. It was all my own idea and it nearly killed me – very nearly broke my spirit – but I’m sure it went some way towards keeping the kilos off. I don’t drink, I don’t eat cheese. I skip ice-cream, hot chips, burgers and pies. The sight of a piece of mud cake can reduce me to tears, worse if it has chocolate icing. Christmas is the hardest, because it’s peak training season. Nationals are in March, so I have to be extra strict at Christmas. And all of this has to come from me. I am the one who has to stick to the regime. Beyond the beady eye of my coach, it is up to me. When I’m at home, when I’m out with friends, I have to be good. I need the willpower of a saint. But I am strong and determined.

“Also, I am convinced I am fat.”

“Whenever I have to stand on the pool deck in my togs, listening to my body being discussed like it’s an engine and not the arms, legs, thighs and stomach of a teenage girl, I am self-conscious and miserable. I think I am just too fat.

“Part of the reason for this is that there is nothing strategic about my diet, nor about the diet of anyone who I know. Despite the ad hoc appearance of dieticians in our lives (such as at the Fukuoka World Championships, where they popped up with that salmon cake), we receive no sustained scientific dietary advice. The only dieticians in my life are affiliated with the QAS, and they’re seen as extraneous: outside help you can seek if you really need to shed some kilos or put on some bulk.

Australia’s Leisel Jones at 2005 world titles – by Patrick B. Kraemer

“They are not part of our ‘team’, not in the way our coach or gym trainer is. And seeing a dietician is on par with seeing a sports psychologist: not encouraged. Back when I swam with Ken, he never wanted us to deal with outsiders – coaches knew best – and his strategy when it came to diet was to put most of the girls in our squad on meal-replacement shakes at some time or another.

“Diet shakes, yeah, that’s a good idea for a teenage athlete! We were always getting weighed in, always being judged. We were actively encouraged to skip meals to lose weight. It is irresponsible and terribly damaging. And it’s a quick way to screw up a teenage girl’s metabolism, to say nothing about the state of her head.

“Even now at the QAS we are all weighed three times a week. Weigh-ins take place on the pool deck in our togs, and we are weighed in front of our squad (girls and guys together), plus a team of coaching staff. There are men there as old as our dads, all watching our embarrassment as we are publicly weighed.

“Even now at the QAS we are all weighed three times a week. Weigh-ins take place on the pool deck in our togs, and we are weighed in front of our squad (girls and guys together), plus a team of coaching staff. There are men there as old as our dads, all watching our embarrassment as we are publicly weighed.

“Weighed, weighed and weighed again.”

It is then that she recounts the “6:1.20” tale.

Awareness: Cate Campbell’s Contribution To Better Culture

Cate Campbell new horizons – Delly Carr Collection

Back in 2015, when Jones was promoting “Growing Up In Lycra“, sprinter Cate Campbell was right there with her, recalling her own issues with look and weight as a teenager in 2008-09. Campbell told the Courier Mail at the time:

“Your physical attributes are often linked to success. You look at the glossy pages of the magazines and the people on TV, they are beautiful and skinny. Your physical appearance is linked with happiness and success — suddenly I was terrified because my success was going to be taken away from me, that I was going to lose it.”

Campbell restricted her diet to around 1000 calories despite the the heavy training loads over four hours a day. For breakfast she had half a cup of oats, for lunch it was a cup of soup, dinner was a small serving of whatever her mum Jenny had cooked the family.

Calorie control was culture. Cate soon heard fly saying ‘You’re looking really skinny’ and ‘you’ve lost weight.”

Affirmation. Not always a good thing. Campbell took the complement and fed on it. She recalled the slide from feeling good to feeling like her body was her enemy.

“I was getting sicker and sicker and sicker,” said Campbell.

Michael Phelps to the rescue. Campbell read a chapter off Phelps’ book “Beneath The Surface”, the one detailing how his sister Hilary had developed an eating disorder. Little bro’s take in his book: “…skinny swimmers aren’t good swimmers.”

Encouraged by her mother, Campbell consulted a dietitian: 10 kilos went in 2011-2012. The sprinter recalled back in 2015:

“I decided then I would be a swimmer and do whatever it takes, after missing the team in 2011, that was two years out of the pool, I decided I would do whatever it took. I decided to be healthy and happy, because I was miserable. I was tired, cranky, sick; all of these things. I never went to a really anorexic or bulimic stage — but it was that psychological bashing that you give yourself. I don’t know where it stems from — but it is so ingrained in society in general.”

Cate Campbell – Delly Carr Collection

Educating young athletes is essential, she said: “It’s something I am telling kids all the time, you want to be fit and strong.

“People get caught up in the idea that health is just what you look like and what you eat, but your health is physical, emotional and mental. Who’s to say eating that bowl of ice cream after training isn’t going to help me psychologically and emotionally? You look at the Victoria’s Secret supermodels, most of them are genetically gifted granted, but are they really healthy?”

More to the point, she felt healthier and happier the moment, in her own words, she realised that “the sum of your worth is so much more than what you look like”.