On The Record with Bob Corb, NCAA National Coordinator of Water Polo Officials

Editorial content for the 2019 NCAA DI Men's Swimming & Diving Championships coverage is sponsored by S&R Sport.

See full event coverage.

Follow S&R Sport on Instagram at @srsportaquatics

Editor’s Note: The 2019 NCAA Women’s Water Polo Tournament is happening—and Swimming World has you covered! Keep up with all the action online or look for #SwimmingWorld on Twitter and other social media platforms.

This year’s women’s water polo championship marked a milestone for Bob Corb, who is stepping down after a decade as the NCAA’s National Coordinator of Officials (NCO) for water polo officials. But he’s not leaving the sport; he probably couldn’t if he tried. After four decades of involvement, starting as a club polo player at the University of Massachusetts, Corb may be retiring from leading one of the sport’s most important collegiate committees, but—and he’d be the first to say it—polo’s in his blood.

Much like the men and women who he mentors and supports, Corb’s efforts the past ten years only draw scrutiny when there’s controversy, which there was when—following the 2018 NCAA women’s final—he published an open letter calling for specific changes to the college game. He then organized officials, coaches and conference administrators to effect concrete changes and ensure that collegiate polo is consistently called the way the rules are written.

Much like the men and women who he mentors and supports, Corb’s efforts the past ten years only draw scrutiny when there’s controversy, which there was when—following the 2018 NCAA women’s final—he published an open letter calling for specific changes to the college game. He then organized officials, coaches and conference administrators to effect concrete changes and ensure that collegiate polo is consistently called the way the rules are written.

It will take time to gauge the results, but Corb plans to see this effort through, albeit in a different capacity. In a recent conversation with Swimming World, he spoke about his extensive background in the sport, the effort he and others have put into creating a comprehensive framework for NCAA officiating, coordinating with FINA, which is undergoing a significant reworking of its polo rules and the enjoyment he’s gotten working with the men and women who whistle while wearing white.

There’s many high points to your career and a number of folks who had a profound impact on you playing water polo—so that 40 years later you’re still involved.

I started on the East Coast at the University of Massachusetts. We were a club sport and pretty good. We could beat any other [local] club, but there were a couple varsity teams. One of them was Brown coached by Ed Reed, the one team we couldn’t beat.

Ed was larger than life back then—he was a guru of coaches and on the NCAA rules committee. If I was going to say anyone was a mentor, it would be him. Which is ironic because he is now Supervisor of Officials for the CWPA, and works with me on the national evaluator group that I created.

That’s how I started back East in the ’70s. You’d go to a tournament. You’d ref a game. You’d play a game. You get out and coach a game. You did it all because that was the run for us.

By the time I got out of college I was a pretty good high school player. I moved to California because that was where water polo was big. Figured out pretty quickly I was not going to be a big-time player, so I started reffing. And I was pretty good at it. I went up through the ranks relatively quickly. Eventually got to be an international referee. Traveled around… not around the world, but I hit 12, or 13 different countries in my career.

That went on from 1980 to 2008. That’s almost 30 years of refereeing around the United States, or a bit overseas. I was approached in 2008 about taking on the national coordinator position. It was a relatively new position [from] three years previously with Bret Bernard running it.

I looked at this as a good segue [because] my career as an international referee was over due to the age limit.

Corb and Brend Villa, four-time Olympian. Photo Courtesy: B. Corb

When it started there wasn’t much to it. I had a small budget. What I inherited was a group of evaluators mostly from the Mountain Pacific [Sports Federation], and then a couple people on the East Coast.

I grew that group to 20 people from around the country, including Jack Horton and Andy Takata. We calculated, one time, that we had 750 years of water polo experience between the 20 of us. And we have former Olympic coaches. We had a pretty good cross section of quality evaluators. Then we went online with the ADVANTAGE website [which contains] rules, tests, evaluations, formalized evaluation process.

[On Deck With Jack Horton, Referee, Coach, Photographer and Life-Long Polo Enthusiast]

And as I said in that article that I talked with Russ [Thompson] about, for the 10 years that I’ve been at it, my mantra has been to increase the consistency in a raw quality of officiating across the United States. Water polo tends to be very California-centric. Because my roots were on the East Coast, I pushed hard not to let that be the case with the referees.

We truly are national referees. We no longer look at ourselves as, “I’m an East Coast ref.” Or, “I’m a CWPA ref.” No, I’m a referee and I referee wherever I choose to, and wherever I’m invited to because I’m an independent contractor. I can pick and choose the assignments that I accept.

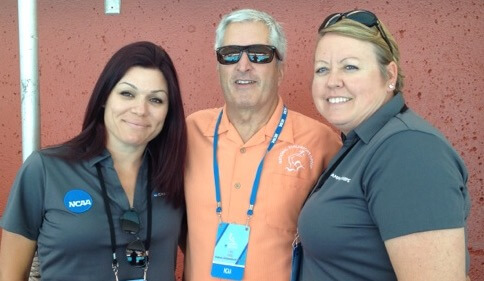

Corb with Danielle Dabbaghian and Amber Drury. Photo Courtesy: B. Corb

When the women’s collegiate game became an NCAA sport, we obviously started recruiting more women into the fold.

The last five years we’ve actually had—for the first time—two women ref the women’s NCAA championship. And just recently a woman refereed the men’s NCAA championship.

I would love for the day to come when that’s not a big deal, but it still is.

You talk about referees being independent contractors. Something I’ve observed is that conferences have their preferences in terms of who they select to referee games.

[Conferences] have a vested interest in putting out the best referees they can. Part of that would be dependent on the level of competition that they offer [or] the compensation they offer. It’s taken from any other sport model, where the conferences tend to have a group of referees that they use on a regular basis. Maybe it’s geographic. Maybe it’s the quality of the officiator that they think they get.

So, the conferences have a vested interest in having a group of referees that they can count on to work the regular season or any of their championships. We’re a very small sport so we only have six water polo playing conferences for the men and seven for the women. And they communicate with each other. The supervising officials are all members of my national evaluating group and they work it out.

I’m a big believer that the best way to do it is: “We want X, Y, and Z at our tournaments. And we’re gonna invite X, Y, and Z.” And if somebody else wants X, Y, and Z also, then X, Y, and Z get to decide which tournament they want to go to.

That’s the free market way of doing things. I’m not sure it always works that way, but that would be ideal. That whole process is something I have no jurisdiction over when it comes to the regular season. My only influence, directly, is the championship itself.

One thing about water polo is—especially at game’s end—whether a referee is willing or not to call certain game-changing fouls.

Every single call you make—and every single call you don’t make—has a direct influence on the game. Whether it’s the first call of the game, or the last call of the game. They’re all important, and the rules should be applied consistently throughout the game.

I fight against [this] consistently. Apply the rules the way they’re written, for 28 or 32 minutes. However long the game is, and then the game is decided by the players in the pool. Not by the referees.

[On The Record with Loren Bertocci; What’s Going on Under Water Doesn’t Matter]

The coordination and organizational impact of simultaneously rolling out rules updates for a national sport appears daunting.

When you talk about trying to organize 120, or 130 independent contractors, referee school was something that I’ve been dreaming about for 10 years, probably longer. We run it every two years, and we run it in conjunction with the new rule book—the NCAA’s on a two-year rule book cycle.

Hadi Farid pulls a red card in 2019 NCAAs. Photo Courtesy: Catharyn Hayne

It’s only been run twice. The first time that I did it I ran it with three sets of instructors around the country. I used a set of instructors that have been trained and worked together. We had PowerPoint presentations. We tried to standardize the delivery. But when you’ve got people who’ve been in this work for a long time, they have their own ideas about what it should look like. Sometimes the message gets garbled.

This time around [last August] we used modern technology. And we had one site, Villanova, where the message came out of, piped in via Skype to the other two sites. It was one set of instructors coming from the same location and going out to the other two sites.

Two years from now we’ll do it again, I hope. And we’ll be a little bit better. The goal is that everybody hears the same message, and everybody goes out and applies the rules as written.

We also gave the coaches every opportunity to watch those videos. They can get on the ADVANTAGE website for free, so they could watch and hear exactly what the referees are being instructed. The idea is to be as transparent as possible, as educational as possible, and as thorough as possible.

You’ve had a decade to make changes. Do you find there is now more consistency throughout the country when it comes to NCAA women’s and men’s varsity play?

I think we’re moving in that direction. We’ve had one men’s season with the clear instruction to apply the rules the way they’re written. And now we’re in our first women’s season.

There’s going to be bumps in the road with that. Watching the men’s season, I think everybody would agree that there were inconsistencies at that beginning, the pendulum swung back and forth. And then sort of found its way towards the middle, where we wanted it to be.

This wasn’t intended to be a massive change. It was a correction, an adjustment in the way that we thought about things. I think most people would say that the game looked different. I was talking to Ed Reed a couple weeks ago, and he said that he was going back and looking at championship video from 10 years ago.

He said, “Bob, you wouldn’t believe how much better the game looks now than it did. It’s just totally different. The stuff we were letting them get away with then, which was in violation of the rules as written—and we weren’t calling—it’s just cleaned the game up tremendously.”

Who’s calling this one?! Photo Courtesy: Catharyn Hayne

I tend to be pretty harsh on myself, so I’m not going to say it’s changed the game tremendously. But I think we’re definitely moving in the right direction.

I’ll add one more thing: I’ve said all along that if we applied the rules the way they’re written, and the game still doesn’t look the way we want it to, then we can change the rules. But why change the rules if you don’t even know if they work? Try them the way they’re written.

That leads to what’s happening in FINA, and the rule changes that have been approved. How do your efforts dovetail with the changes that are now being made by FINA?

From a referee perspective, we always hoped that we could have one set of rules. And we were moving in that direction until recently when FINA adopted their new rules. The NCAA can’t do that, even if they want to. They can’t change anything for another year because we’re on this two-year cycle and this is the first year of that cycle.

The committee will take a look at what FINA’s doing when they meet next year, and put it out to those concerned. Mostly the coaches and the referees, and ask: “What do you think of these ideas? [Do] we want to adopt some of them?”

By then we’ll have a better idea if what we’re doing is working, and whether we need to tweak anything. I talked to Mark Koganov about this. We’re on the same page in terms of what we want the game to look like. We want to clean up the physicality. We want to create more movement on the perimeter, and give athletes a chance to show their athleticism.

[On The Record with FINA’s Andrey Kryukov; Water Polo’s Future Rests on Him]

Make the game easier to understand, so the fans are saying, “Wow wasn’t that amazing?” Instead of: “What was that call?”

We both want that same thing. We’re just going about it differently. There are some things that they’re doing that I hope we’ll want to adopt because I think they’re good ideas. And it’ll be a give and take with, the goal being—at least from the referees’ perspective—“Let’s see if we can get so close together that it’s indistinguishable.”

So, I can walk from one game, swim to the rules to the next. And it’ll be seamless.”

After last year’s NCAA women’s final, you put out a letter saying that the game needs to change—and put it on yourself and your committee to change it. How has that worked out?

The only thing that I would qualify that with is: I was saying what other people had said to me. I try very hard not to take a stand on what I see in the game because I think my role as a referee is to be a neutral arbiter— not take sides, so to speak.

But I could see both sides of the argument. On the one hand, it was a very physical, but at the same time to be that physical in the water you’ve got to be athletic.

Does it have to be one or the other? Can it be both? And can we do a better job of it being understandable to the average fan? In concert with what the rules’ committee had already decided that previous December, it made sense to put something out there that’d start the process of making these changes.

I thought I did a pretty good job of outlining not only the need to do it, but also what we were going to do, and how we were going to do it. I spent from January to September doing that. I was on the road. I went to coaches’ meetings. I went to JOs. Wherever I could platform and say, “Here’s what we’re doing. Be ready.” And for the most part the coaches were prepared for it.

No doubt about it; water polo is physical. Photo Courtesy: Catharyn Hayne

In fact, the coaches’ association came out and supported what we were doing. I think that was the first time that I ever remember that the coaches ended up agreeing on anything. So that was pretty cool.

Some say: “Fighting is killing the game.” I don’t see that. As I understand it, the game has been surviving pretty well with blips here and there since the 19th century.

Before we do that, let me go back and speak to just what you said in terms of the game being … I don’t want to say indestructible, but having survived lots of different innovations, and movements in different directions.

We have to remember that different levels of water polo have different interests in mind. I think at the age group level, it’s all about getting the kids excited about something and having fun. At the collegiate level, it’s about participation, and educational advantages.

But at the FINA level, it’s about television. It’s about selling a product. Not that that’s not important at all levels, but it’s way more important to them to have something that television can address.

Our sport as it was, wasn’t very television friendly. I remember Mark telling me that they did a study of how many minutes of actual water polo got played in an hour, and it was some really short amount. When you take away the time swimming down the pool, nothing’s happening. We’ve got to recognize that sometimes that’s going to impact how our rules look.

There’s an extremely popular televised sport which has thrived despite long stretches of no scoring: soccer. And what do people know about soccer? That the players often flop! And now there’s a flopping foul in water polo.

With any new rule that we put into existence, it takes a while to figure out how to apply that rule. And simulation’s probably the best example we’ve had in a few years of that. What do we mean by simulation, when do we see it and how do we punish it, et cetera?

We’ve made it into a rule, but I think we’re trying to operationalize that. I’m getting ready to sit down with a coach who’s been collecting clips about simulation for a year now. He and I are going to look through them and come up with a short video on what is simulation, and when should it be called. Because there are other factors.

[For instance] the advantage rule: if somebody simulates, but to call that foul then would not necessarily lead to good management of the offensive team if the defense is doing it. So, it’s a lot more complicated than it looks.

And the women are going to be more challenging than the men because of the suits. Because you can grab suits, things could look like simulations that are not.

[The] first issues you deal with—any time you’re thinking about changing a rule—is not everybody agrees that it needs to be changed. There’s an educational process about when and why do we need this rule.

I use this metaphor: If you’re driving 68 miles an hour in a 65 mile an hour zone, you’re breaking the law. But if I’m the cop, I’m not looking for you. I’m looking for the guy who’s going 80. So as referees, I’m not as concerned about the guy who’s going 66, I want to catch the one who’s going 80.

One thing I would throw in is—it’s not a defense of the referees, but it’s an explanation. They only get to see it once, live time, real speed, game speed, and then they have to make their decision in a flash of a second. Sometimes, there’s going to see what they’re going to see quickly. It’s not what they would see if they got to watch a video shot from a different place, in slow motion, repeated 16 times, run backwards. Sometimes, in retrospect, a referee will say, “Yeah. If I’d seen what I see now I would have made a different call.”

As a spectator, when you see something unusual you connect it to a moment of action, and assume that the referee is as subjective as you are.

Maybe referees do change a little bit, but I also think coaches think that’s happening, and there’s a confirmatory bias there. They think it’s happening so they see something and go, “Yeah. There it is.” And then they communicate that to their players, who then play scared.

The fans start to pick up on it, and now they start yelling at the referees. So why is it that the referees are considered the culprit when there’s players and coaches that are also involved? I get a little sensitive about that because I think: “Who’d want to referee under those conditions?”

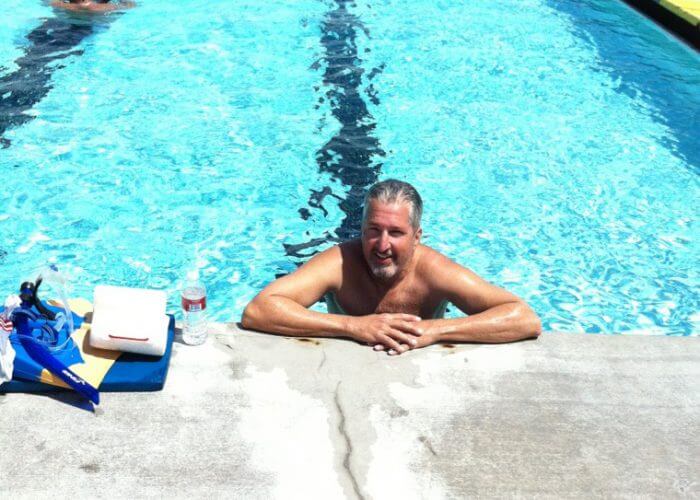

This is the life… Photo Courtesy: B. Corb

I once got to sit with John Wooden and asked: “How do you deal with referees?” And he said, “You know the worst referee I ever saw made a call at the other end of the court. And he came down and he stood in front of me. And I was mumbling, rumbling, and telling him how horrible he was. And he looked at me and he goes: “John, they loved it at the other end.”

Your thoughts about being at NCAA for the last time, and what are you going to look at as your last responsibility as coordinator of officials?

Every championship that I go to, I have two goals. One is for the referees not to be an issue, and two is for the referees to feel respected and appreciated for what they do. I see that as being my primary mission when I go into NCAA championships because you’ve got five, or six, or four, whatever number of the best referees in the country. And this is the one time when they should feel honored and respected for being there.

My two favorite nights of the year are the Saturday night of each of the championships because I take all the referees out to dinner, and we celebrate what we’ve accomplished that year.

In terms of the referees not being an issue, obviously there’s going to be discussion about referees, and who got assigned, and which refs are doing which games, and everything. But I don’t want the discussion to be about referees. I want it to be about the game.

The way I look at it is, not so much are they invisible—because, clearly, they’re going to be visible—[it’s] are they noticeable? I want the referees to not be noticed. And the way that you do that is to referee a game that’s consistent with the way the rules are written, and then work collaboratively with your partner so that there’s a seamless coverage of the pool that gets the call right regardless of who makes it.

What happens now, assuming you’ll keep doing what you love in some other form?

As a psychologist, I always ask my clients when they’re making a big decision: “Are you running away from something, or are you running towards something?”

Start polo teaching young! Photo Courtesy: B. Corb

I ask myself the same question, and it’s not either or, it can be both. I definitely don’t think I was running away from anything other than I put in a lot of hours over the last year, and felt I was not getting to do some of the other things I like to do. So that was my primary reason for stopping this job. Water polo’s in my blood. It’s not going anywhere. One of the things that I miss doing is coaching—so I’m actually coaching again. I’m going to coach an 18 and under girls’ team.

One way I’ll stay involved [is] USA Water Polo’s asked me to be involved in their evaluation system. I’ll stay part of the national evaluator group, as a member as opposed to the head of it. And then we’ll see what else pops up. I may start refereeing again. Not at the highest levels but just at the age group levels. There’s nothing more fun than going down and reffing a 10U, or 12U game, and having parents walk up to you and say, “We’re glad you’re here.”

We put our novice teachers, our novice referees, with our novice players, and our novice students, you know our kindergarten students. And it’s so backwards. Our best teachers should be teaching in the first grade because that’s where the kids learn to learn. I used to teach psychology at a university for four years. I [would] put up a sign that said: “I teach for free. I get paid to grade.”

For me, teaching college students, or heading up the highest level of referees—that’s an honor. That’s a privilege. It’s getting down to the grass roots, and working with the younger kids, and the younger refs, that we really need to focus on.